Her friends and family think Mimi is a great catch; she is beautiful, affectionate, and very smart. Sadly, she is better at attracting intimacy than keeping it. She blames her history of failed relationships on her “loser boyfriends who are always staring at other women.” Their attribution for the relationship’s failure is that her jealous rages drove them away. Mimi hates it when her friends try to help by offering advice because “they don’t understand.” The advice they give her doesn’t ring true because they only see how it looks from the outside; they don’t have access to the experiences that drive her reaction. Alas, as her track record shows, Mimi doesn’t understand her puzzle either because she only experiences how it feels from her first-person perspective, and, at that moment, her understanding of what is true is distorted by her intense emotional state. To know herself well enough to solve her puzzle, she has to observe the sequence of external events [the things that happen] and her subjective reaction from two perspectives: How it looks from the outside and how it feels from the inside.

Mr. E. can usually figure out how to arrange things to get what he wants. But in contrast to his uncanny ability to predict and control the events at his office, he can’t control himself. While he may appear successful to his friends and coworkers, he feels like a failure because he is on the verge of losing everything that matters to him. He attributes his disastrous financial and marital situation to his bad luck at the casino, but from our third-person perspective, he seems blind to the true cause of his problem.

These cautionary tales illustrate two versions of the puzzle of voluntary self-sabotage: an individual with a particular biological predisposition and conditioning history encounters a high-risk situation, such as a crisis of stress or temptation, and chooses the path that they have already discovered leads to an unwanted outcome. Each time this happens, they realize they made the wrong choice, but that doesn’t stop them from making the same mistake the next time they get the chance.

The complication that prevents them from taking advantage of recognizing their error is that it doesn’t come until later. When they commit the error, it seems like the right thing to do. It is only later, when they look back on it from the third-person perspective of hindsight, that they realize it was a mistake. They don’t benefit from their painful education because the next time they react to a provocative situation, they will interpret it from the first-person perspective.

Emotional and motivational reactions emerge from the first-person perspective; we can predict that the next time they encounter a high-risk situation, state-dependent distortions of perception and judgment will affect their choices in a manner similar to the past. How can we use this forewarning to prepare for the inevitable encounters with the stressors and temptations that the future holds? The first task is to solve the puzzle inside the enigma of voluntary self-sabotage.

Different ways of framing the puzzle suggest clues to its solution:

- Why do competent folks, who can usually figure out how to get what they want, repeatedly fail to solve this important yet seemingly simple problem?

- Why don’t they use the same problem-solving skills that enabled them to solve other difficult problems to solve this one?

- Why doesn’t their success rate improve with experience?

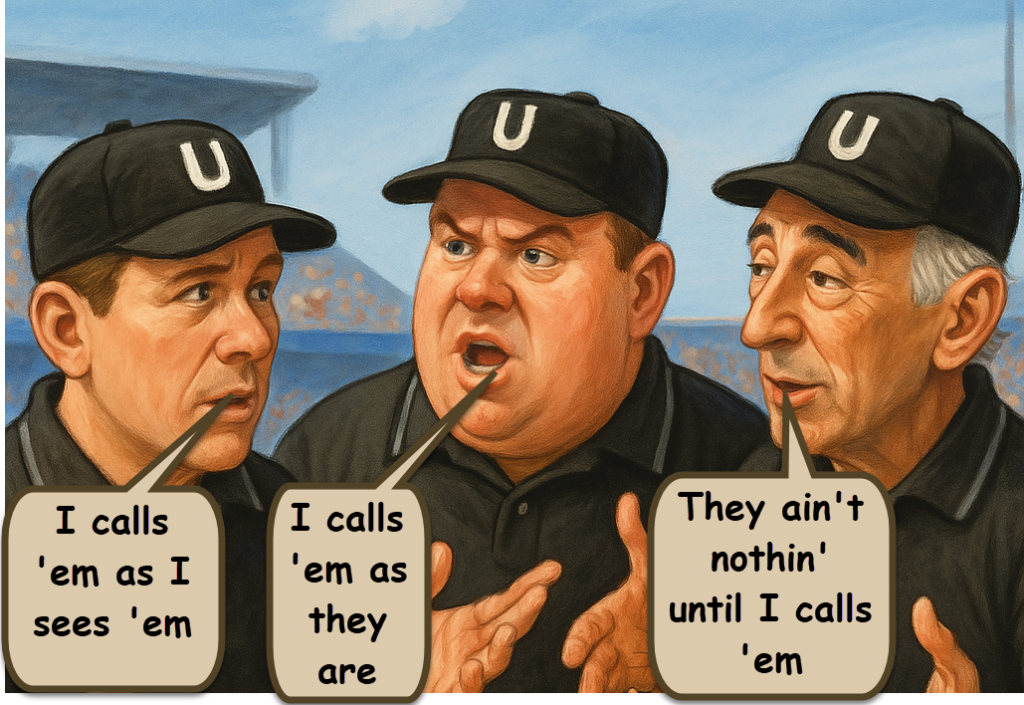

- Why is the critical error of judgment that is so obvious to most observers invisible to the one who makes it?

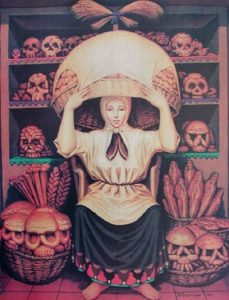

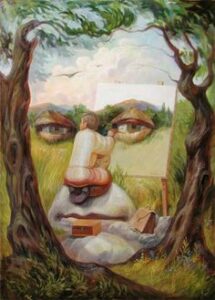

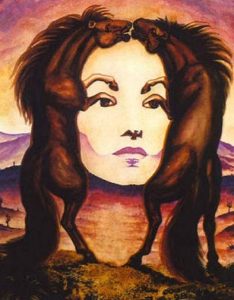

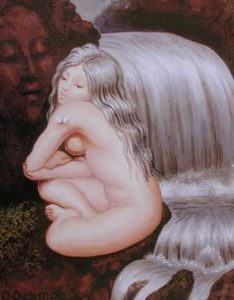

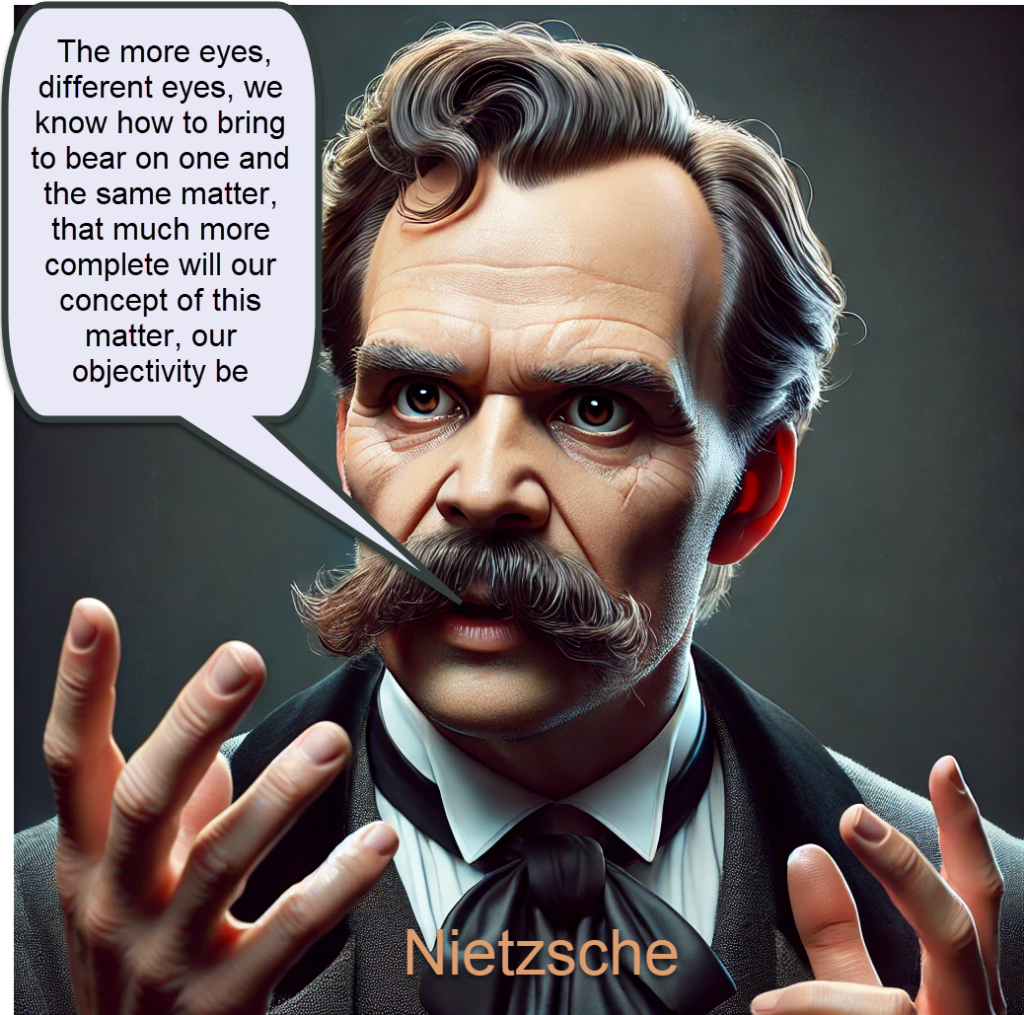

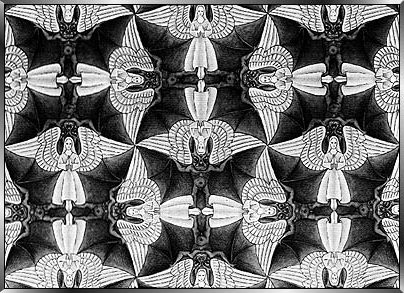

If you can detect a recurring pattern of voluntary self-sabotage in your personal history, you have a puzzle to solve. Evidently, your conventional problem-solving strategies don’t work on this one, so you’ll have to try a different approach. The problem of voluntary self-sabotage is difficult to solve because it contains a puzzle within it: A soul’s reaction to an event that happened looks different than it feels. The truth about cause-and-effect is not available from either perspective. Friends, family, and treatment providers only have access to the third-person perspective of the problem. Their solutions tend to be simplistic, obvious, and ineffective. The solutions that our heroes generate during high-risk situations tend to be simplistic and wrong. Solving the enigma of voluntary self-sabotage requires a collaboration of both perspectives. To become familiar with this kind of collaboration, I invite you to explore the transformation of objective reality [pixels on the screen] into subjective experience [images].

The implication of his recurring pattern of failure is that the future will be like the past. Unless he finds a way to know himself well enough to use the principles of cause-and-effect to bring about outcomes that are in harmony with his interests and principles.

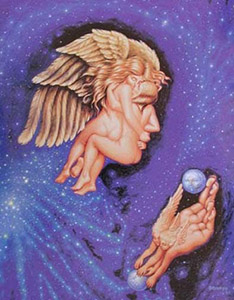

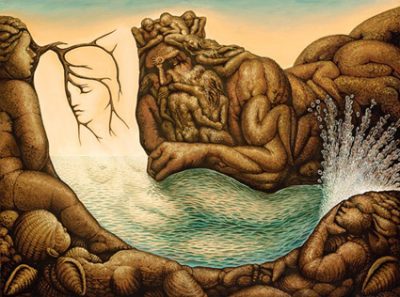

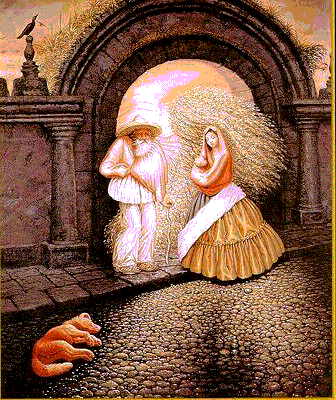

The implication of his recurring pattern of failure is that the future will be like the past. Unless he finds a way to know himself well enough to use the principles of cause-and-effect to bring about outcomes that are in harmony with his interests and principles.  The brilliant Mexican artist Octavio Ocampo has given us a gift: His ambiguous creations are so artfully executed that we automatically accept our first interpretation as valid… until we parse the pixels in a different way to create a different interpretation. The recognition that images don’t exist on the screen but are created in the mind is an insight that applies to our entire perception of reality.

The brilliant Mexican artist Octavio Ocampo has given us a gift: His ambiguous creations are so artfully executed that we automatically accept our first interpretation as valid… until we parse the pixels in a different way to create a different interpretation. The recognition that images don’t exist on the screen but are created in the mind is an insight that applies to our entire perception of reality.