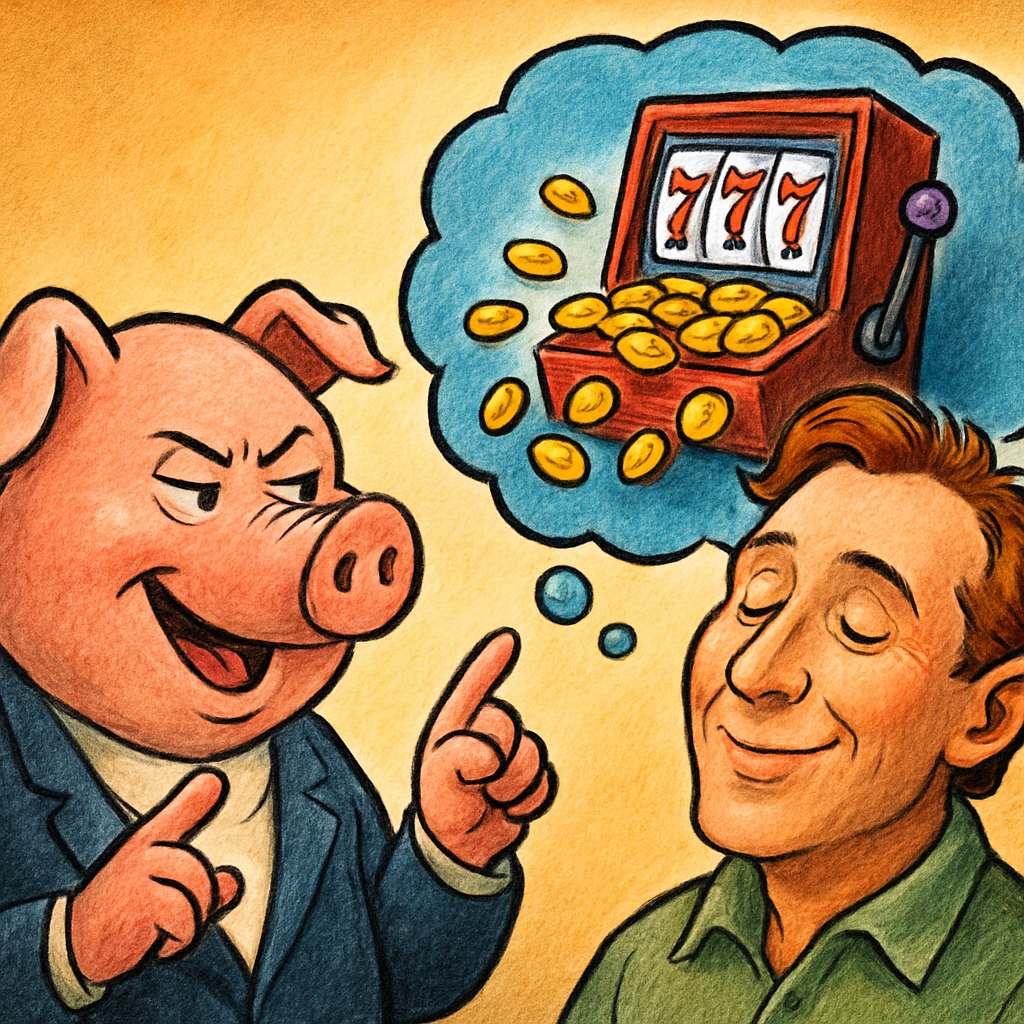

A farmer’s wife is in the kitchen doing the dishes when her husband walks in carrying a goat.

He says, “I want to introduce you to the pig I’ve been fucking.”

She says, “You moron, that isn’t a pig, it’s a goat.”

He says, “I was talking to the goat.”

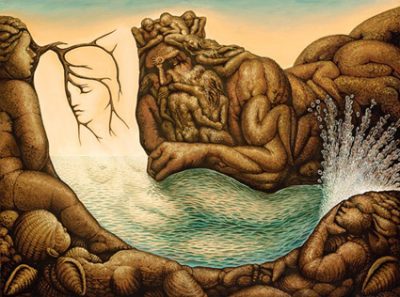

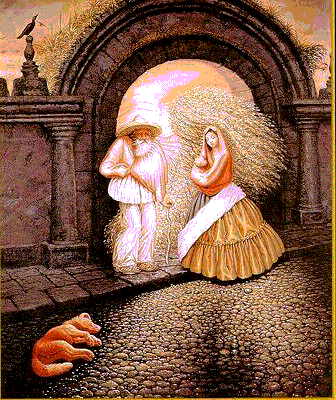

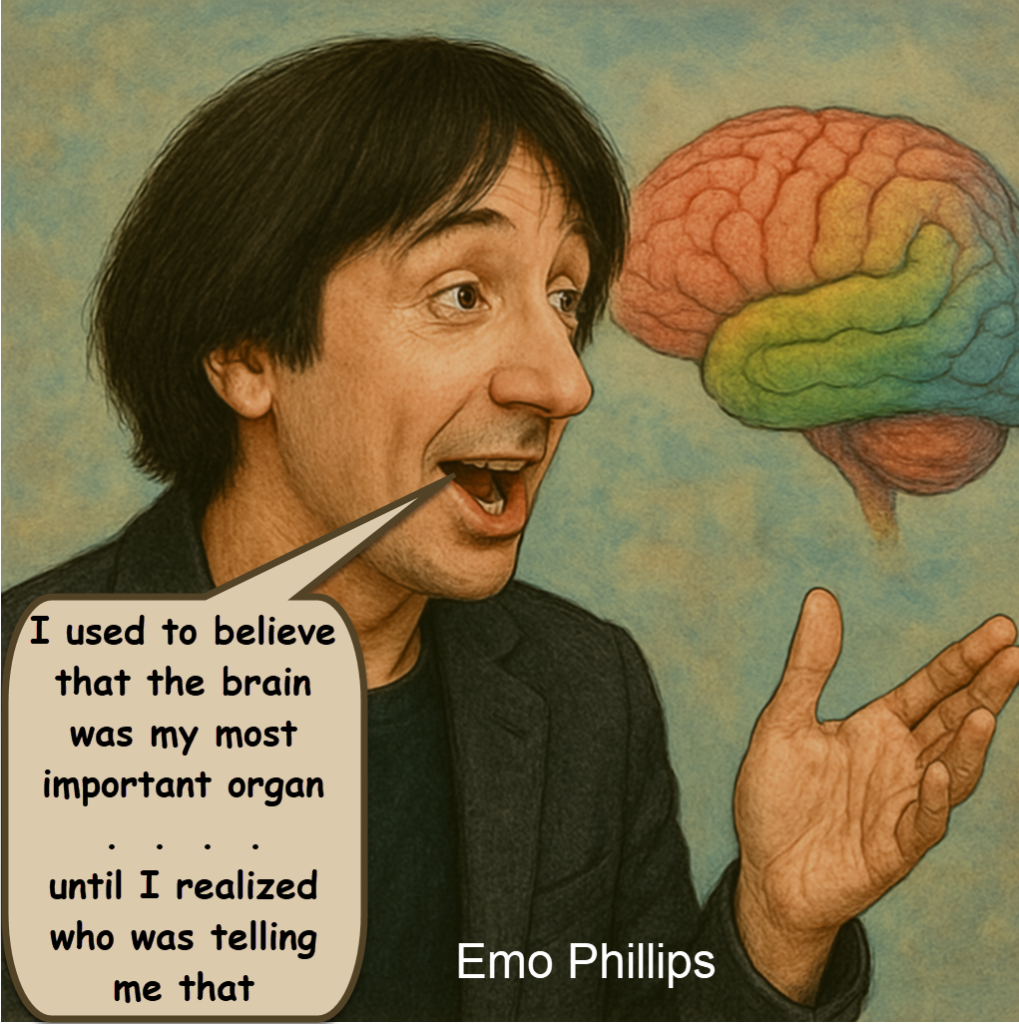

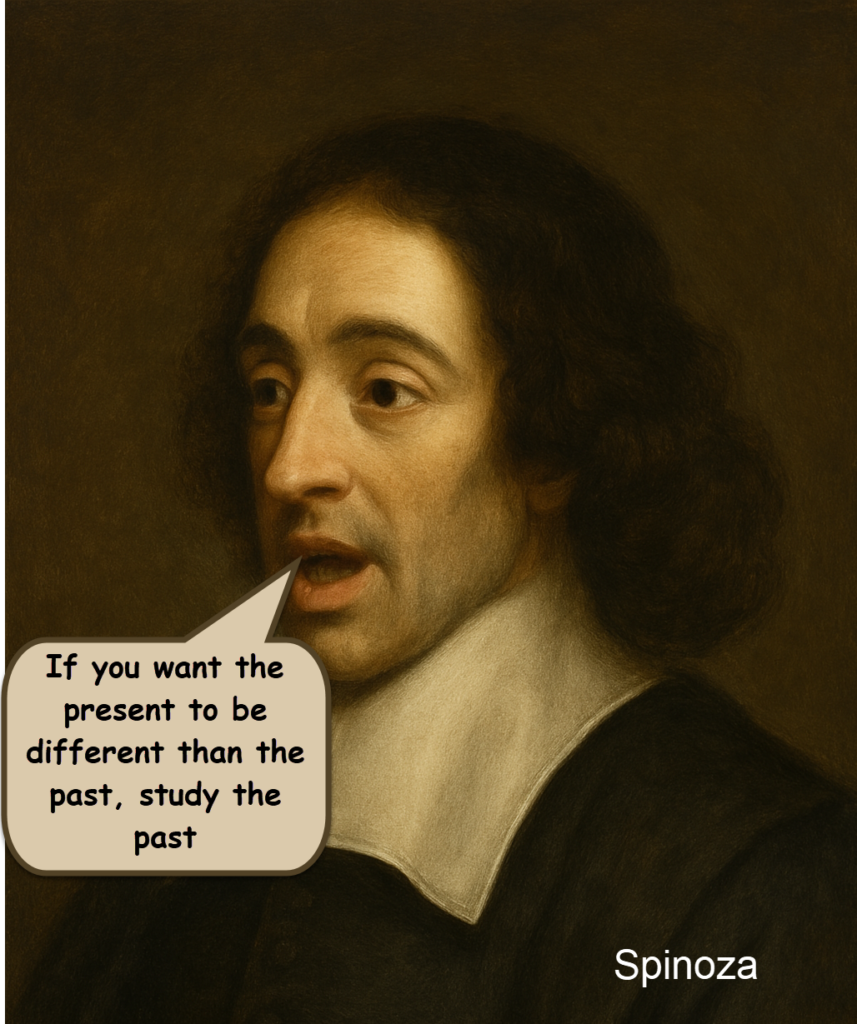

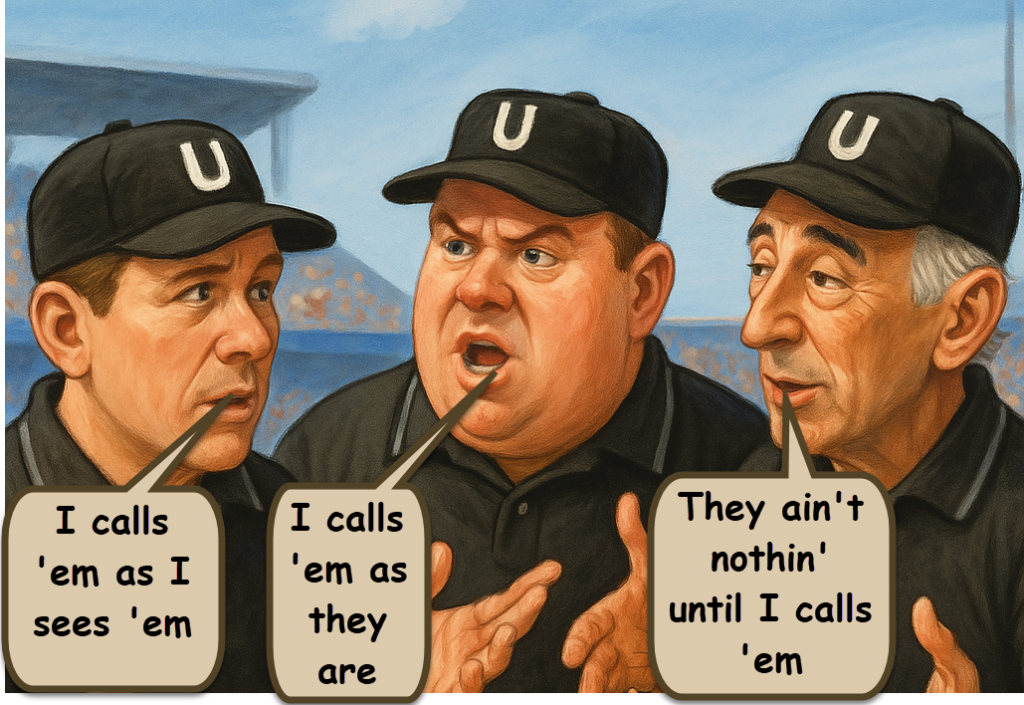

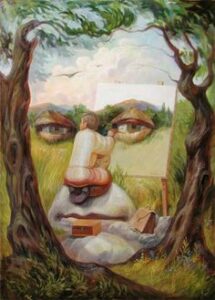

I hope you weren’t offended by this off-color joke. I presented it for the same reason I showed you Ocampo’s artwork: To give you the opportunity to observe — from the two research perspectives — the subjective experience of getting a joke. So, recall the moment that you realized that your initial interpretation of the farmer’s statement was wrong, and observe this moment from the first-person perspective of the subject in a study of the psychology of humor; then observe that same moment from the perspective of the researcher. As the subject, notice that you experienced a subjective reaction to the reveal of the true meaning of the farmer’s statement. As the researcher, notice that the reaction to the punch line required that the subject had first been set up to misinterpret the farmer’s statement. For more examples, examine your memory of past reveals, such as the twist at the climax of a detective story or the reveal of how a magic trick was performed.

The researcher might conclude, for example, that the wonder you experienced watching a woman wiggle her toes after a magician sawed her in half was due to the incongruity between what you knew to be true (you can’t wiggle your toes after you’ve been sawed in half) and what you just saw with your own eyes. Likewise, your reaction to a well-set-up joke may be attributed to the incongruity between what you initially assumed to be true and the truth revealed by the punch line. The subjective reaction indicating surprise shows that the entertainer’s artful setup was successful in taking you in. In the future, you can derive more than entertainment from jokes, magic shows, and other reveals by using the reaction they elicit as first-person reminders of how easily you can be taken in.

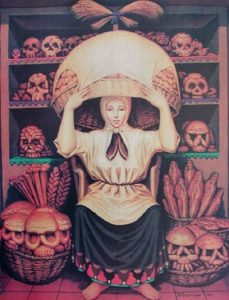

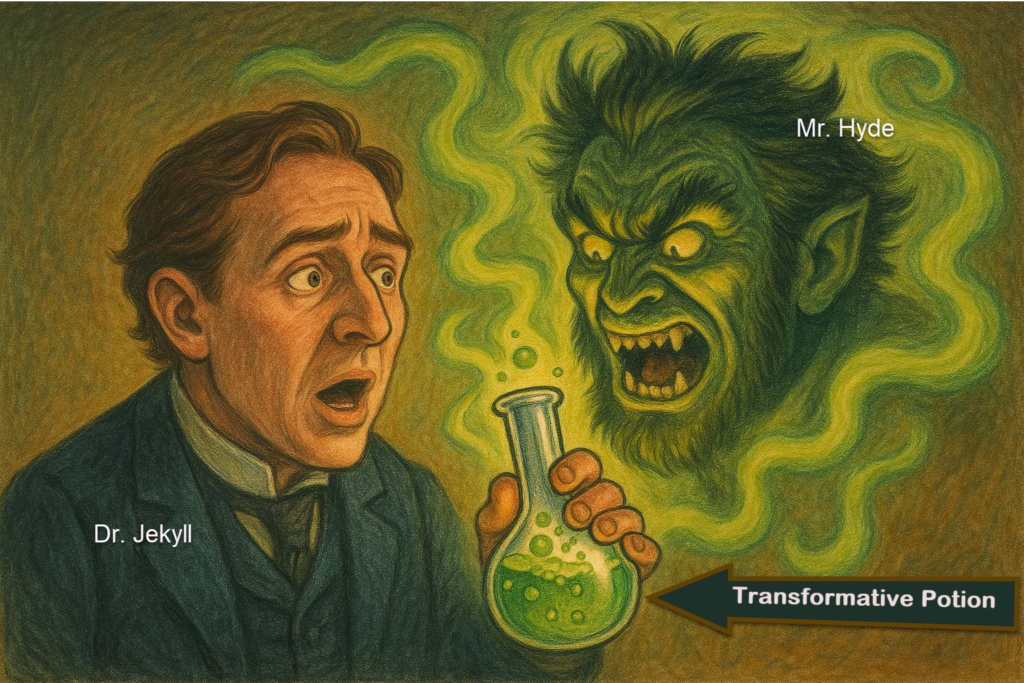

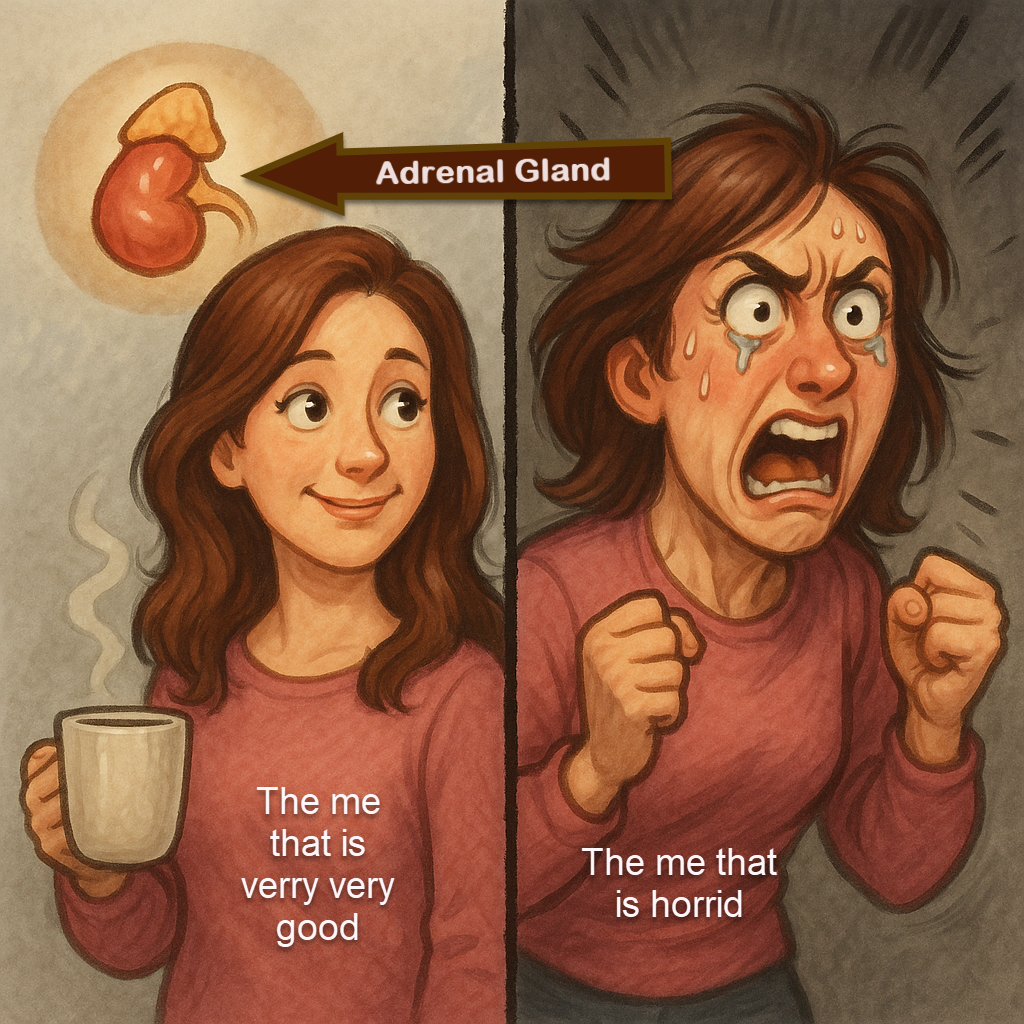

Knowing yourself from the outside is different than knowing yourself from the inside. If you were aroused by some of Ocampo’s graphics, it wasn’t the pixels that were arousing; it was the images that you transformed those pixels into. Likewise, Mimi’s emotional reaction to her boyfriend’s tardiness wasn’t provoked by any single stimulus element but by the subjective reality she created from the totality of inputs received by her nervous system.

You’ve understood that the map is not the same as the territory since you were a kid, but that abstract knowledge hasn’t prevented you from being taken in by politicians, salesmen, and, most importantly, by your own dogmas, as illustrated by the ones that ruin the lives of Mimi and Mr. E. To prepare you for the high-risk situations your future hold in store for you, requires that you know yourself at both the abstract and experiential level — to understand how cause-and-effect unfold from both third- and first-person perspectives.

During your future high-risk situations, you will react to what you regard as reality. Your subjective reality at these critical moments will be state-dependent; the reality you are experiencing now [given that you have the luxury of time, cognitive resources, and distance to consider things from the third-person perspective], isn’t. Put another way, from the first-person perspective, there is no difference between subjective reality and objective reality; from the third-person perspective, there is. To react mindfully to the things that happen requires the collaboration of both your first- and third-person perspectives.

.

.

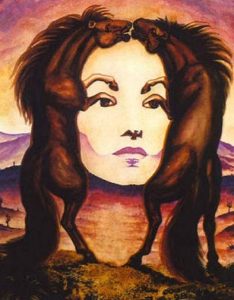

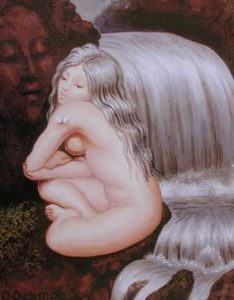

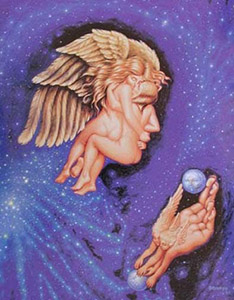

The brilliant Mexican artist Octavio Ocampo has given us a gift: His ambiguous creations are so artfully executed that we automatically accept our first interpretation as valid… until we parse the pixels in a different way to create a different interpretation. The recognition that images don’t exist on the screen but are created in the mind is an insight that applies to our entire perception of reality.

The brilliant Mexican artist Octavio Ocampo has given us a gift: His ambiguous creations are so artfully executed that we automatically accept our first interpretation as valid… until we parse the pixels in a different way to create a different interpretation. The recognition that images don’t exist on the screen but are created in the mind is an insight that applies to our entire perception of reality.

Ironically, the fiction she is so certain is true becomes true because she regards it as true. Attempts to help her reason her way out of her trap work out as well as you might predict;

Ironically, the fiction she is so certain is true becomes true because she regards it as true. Attempts to help her reason her way out of her trap work out as well as you might predict;